DISCLAIMER

In early 2022, I published a three-part series related to the topic above. Writing the articles took several months before they were ready for publication. I won’t delete these original texts, as I consider them the first edition. However, since then, certain changes have allowed me to update the content with new information. First, the emergence of more reliable AI language tools has helped me improve grammar, syntax, and flow, while preserving the original ideas and creativity. Some parts of the original text were vague or difficult to understand and required revision. Second, new data has surfaced, further supporting the points I made back then in a clearer and more impactful way. Lastly, the topic itself has gained significant traction in the post-pandemic world, where we are seeing an overwhelming spread of pseudoscientific and anti-intellectual content.

INTODUCTION

Dear friends and readers,

In today’s rapidly evolving world, there has been a noticeable rise in public resentment and misconceptions surrounding core scientific principles—especially in the last 20 years and most recently during the first pandemic of the 21st century [1] . On one hand, it is crucial to foster a deeper understanding of scientific endeavors, their significance, and the rigorous process behind scientific inquiry. On the other hand, it is alarming to witness the widespread ignorance and misuse of scientific knowledge. The stark lack of understanding of natural processes, coupled with the confusion between correlation and causation, is not only concerning but downright infuriating. It feels as though we are hurtling toward a society reminiscent of the dystopian film Idiocracy [2], with potentially dire consequences looming ahead. The sooner we address this issue and cultivate a clear understanding of scientific literacy, the better chance we have of avoiding the catastrophe that may await us. I hold hope that the essential level of scientific literacy has not been entirely lost, which would enable us to approach and solve real-world issues from a scientific standpoint. However, identifying and defining the patterns underlying this growing social problem remains a challenging task. Initiating a thoughtful and critical discussion on this matter is of utmost importance, as scientific illiteracy persists among a significant portion of the population, including individuals with higher education. I acknowledge that this observation may lead to disagreement or misunderstanding. My intention is not to engage in ad hominem attacks or to undermine anyone’s intelligence. Instead, I aim to address the irrational interpretations of reality sometimes exhibited by scholars and scientists themselves. It is often assumed that scientific literacy and critical thinking are interchangeable, yet they are distinct concepts. In the following text, I will clarify this distinction.

It is important to note that individuals may excel in critical thinking within specific fields while lacking scientific literacy in others—or in general. It is not uncommon to encounter highly educated individuals who are scientifically illiterate, a claim that may provoke differing perspectives. Furthermore, I wish to distinguish between those who have not had the opportunity to become scientifically literate despite their education, and those who have had the opportunity but failed to fully embrace it.

Short excurse about core sciences

I propose distinguishing between true scientific disciplines and academic disciplines. Scientific disciplines generate fundamental, transformative knowledge largely on their own, without relying heavily on other fields. They can also predict outcomes independently, without needing immediate input from external domains. This autonomy defines their unique contributions. The core sciences—mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biology (including their subfields)—exemplify true sciences. They explain natural phenomena and make independent predictions, serving as the foundation for other academic areas. For example, physics applies mathematics, chemistry builds on physics, and biology relies on chemistry, illustrating the interconnectedness of these core fields. In contrast, academic disciplines such as social and applied sciences depend on the core sciences for paradigm-shifting discoveries. Many cannot independently produce long-term empirical predictions or mathematically based explanations. Applied sciences use scientific knowledge for technological advancements, while social sciences study human behavior and interactions. Although social and other academic disciplines may not qualify as core sciences, their value should be recognized. Understanding their roles and interdependencies enhances our comprehension of the scientific landscape. This distinction also raises questions about the classification of academic activities within universities. I propose reserving the term “faculty” for scientific disciplines, while social sciences (e.g., law, politics, economics) could form academies, and applied fields (e.g., medicine, engineering) could be categorized as colleges. Some colleagues, especially in the social sciences, may disagree, but such opposition often stems from subjective preferences rather than objective reasoning. For example, classifying theology as a science is sometimes more political than scientific. My argument is not biased against social sciences but is based on a rational evaluation of what defines a true science.

Even respected figures in the scientific community can demonstrate a surprising lack of scientific literacy on certain topics, even within their own field. This includes prominent scientists and scholars who, despite benefiting from scientific advancements, may hold misguided views. For example, scientifically illiterate arguments are often found in religious apologetics. Humans are naturally inclined toward irrationality, which isn’t entirely negative. It can be seen as a byproduct of evolution, sharpening our instincts for survival in certain situations. However, excessive irrationality can lead to flawed reasoning, unfounded fears, and ideological biases. These tendencies flourish in times of fear and ignorance, often dormant during stable periods (e.g., peace, social security, absence of natural disasters), but they become pronounced during crises (e.g., war, social insecurity, natural disasters).

A lack of understanding of fundamental natural laws [3] —whether in physics, chemistry, or biology—can deepen our fear of the unknown. This often results in accepting unverified claims as established scientific facts. Unfortunately, such thinking opens the door to demagoguery and the acceptance of empty rhetoric and illogical arguments.

Before I continue, I’d like to clarify a few things about myself:

I do not have formal higher education in the natural sciences. While I attended a high school focused on energy production and electrical engineering, pursued the study of astronomy, and come from a family with a strong background in natural and applied sciences, I don’t consider these experiences as significant scientific influences. However, this doesn’t weaken or affect the arguments I’ll present. I’m addressing how to identify a scientifically literate person and how to develop scientific literacy, especially in areas related to the natural sciences. These skills begin forming during childhood and elementary education, not in higher education. Advanced academic qualifications can be helpful but are not the primary factor.

As a passionate amateur scientist, I constantly strive to improve my own scientific literacy, learning to recognize my own biases and avoid pseudoscience. I don’t claim to be a chemist, physicist, or biologist, but scientific literacy doesn’t mean expertise in specific fields. Instead, it involves understanding the general principles that help us assess what is plausible or scientifically valid. In short, formal higher education does not guarantee scientific literacy. Many highly educated individuals, even with multiple doctorates, may lack true scientific literacy due to various factors.

To explain the rationale behind these “self-descriptions,” it’s important to address the handling of criticism and suggestions. Unfortunately, instead of factual or logical rebuttals, I often encounter ad hominem arguments and attempts to discredit my formal expertise in the subject. I will address this type of fallacy later. This issue often comes from individuals who are scientifically illiterate but overly confident in their knowledge—a key trait of scientific illiteracy. It reflects a refusal to accept criticism or recognize faulty reasoning. To preempt unrelated refutations, I outline my formal qualifications here. However, I fully welcome well-founded factual criticism, as openness to scrutiny is essential to scientific thinking.

Susceptibility to nonsense. Why? – no one is excluded!

Let me begin with a quote from astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson:

“Scientific literacy is an intellectual vaccine against the claims of charlatans who would exploit ignorance.”

Scientific literacy involves understanding fundamental scientific concepts and the ability to critically evaluate scientific information. It’s important to distinguish between three types of reasoning: common sense, critical thinking, and scientific literacy. Scientific illiteracy refers to a lack of understanding of basic scientific concepts. Notably, even individuals with higher education may not necessarily possess scientific literacy, so assuming advanced education guarantees it is both inaccurate and a logical fallacy.

Common sense is an invaluable cognitive tool that helps us navigate everyday life. It enables us to make sense of the world based on personal experiences, a skill deeply ingrained through evolution. However, common sense is subjective and can vary from person to person. While shared experiences exist, conclusions drawn from common sense should be approached with caution, as they may not align with scientific evidence. For example, common sense may mislead us by confusing correlation with causation, leading to incorrect assumptions. It is crucial not to confuse common sense with critical thinking, as they are distinct concepts. While common sense is often emphasized, particularly in everyday situations, it may prove inadequate when exploring more complex or abstract topics, such as the physical world. As physicist Stephen Hawking once stated: “Although our apparently common-sense notions work well when dealing with things like apples, or planets that travel comparatively slowly, they don’t work at all for things moving at or near the speed of light.” [5]

Common sense is also easily influenced by superstition and personal beliefs, which can oversimplify complex issues. Take, for example, the topic of electromagnetism and its potential health impacts. People often confuse electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with electromagnetic fields (EMF), treating them as the same. There’s widespread misunderstanding about which forms of radiation are harmful and which sources emit significant energy. For instance, some believe WiFi electromagnetic waves are harmful, even though radiofrequency (RF) waves, like WiFi, are generally safer than other forms of electromagnetic radiation, such as infrared (IR). The misconception persists because heat—associated with IR waves—feels tangible to us, while RF waves do not. Both IR and RF waves are non-ionizing and considered safe under normal conditions, though IR has more energy per photon, making it capable of causing burns in concentrated forms. Misjudgments like these often stem from personal experience rather than scientific evidence. Consequently, it is not advisable to place one’s hand on a hot stove, where concentrated IR radiation is present. Conversely, it is generally safe to touch and be surrounded by multiple WiFi routers emitting RF waves.

Critical thinking, on the other hand, involves a deeper and more rigorous examination of issues. It requires not only understanding the relevant scientific data but also being aware of potential cognitive biases. It encompasses a profound and meticulous examination of subjects within a particular scientific or thematic domain. Critical thinkers apply logical reasoning and thorough analysis to navigate complex intellectual landscapes. While critical thinking is an essential skill within our primary field of interest, it is crucial to remain open-minded, particularly in unfamiliar scientific areas. Without this, we risk relying on personal beliefs instead of objective facts. Even great thinkers, like Immanuel Kant, were occasionally limited in their understanding of natural processes and medical advancements. While Kant was a brilliant philosopher, some of his ideas on natural science seem outdated by modern standards. This highlights that even critical thinking has its limits when it comes to scientific literacy.

Scientific literacy, however, goes beyond critical thinking. It is a multifaceted skill, particularly evident in children. As an educator, I often observe how children approach questions without preconceived notions or biases. Their open-minded curiosity is inspiring. Unfortunately, many children lose this ability as they grow older due to factors like flawed educational systems, religious indoctrination, or political influence. As adults, their thinking may be limited to common sense or, at best, critical thinking in specialized areas. However, if scientific literacy survives into adulthood and is cultivated, it becomes a powerful polymathic cognitive skill. A scientifically literate person can recognize key facts, systems, and the broader importance of any topic. They can also detect confirmation bias and cognitive dissonance. A particularly apt definition of scientific literacy is: “the knowledge of key science concepts and the understanding of scientific processes, including their application to cultural, political, social, and economic issues.”[6]

Scientific literacy empowers individuals to analyze and interpret information effectively. For example, after witnessing a catastrophic plane crash, our common sense reaction might be fear-based: “Flying is dangerous.” However, with critical thinking, we can look at the broader context. Statistically, flying is one of the safest modes of transport. Scientific literacy, in particular, adds another layer to this reasoning. To understand the incident accurately, we would ask: What kind of plane was it? Was it a large commercial jet, like an Airbus A380, or a smaller aircraft? Were there passengers on board, and what credible evidence supports the claim of fatalities? This type of analysis, characteristic of scientific literacy, allows for a more nuanced understanding.

The distinction between causality and correlation is crucial in practical situations, going beyond mere philosophical debate. A scientifically literate person can identify when an argument relies on faulty reasoning. For example, if someone claims that a particular medication caused harm to their child, it’s essential to recognize the logical fallacy in generalizing that it will harm everyone. Scientific literacy encompasses not only critical thinking but also the ability to analyze data objectively, distinguishing it from other cognitive processes. Here is an example of such fallacy:

- To use one’s own experience, or the experiences of others with similar characteristics, as a benchmark in this case is simply anecdotal evidence. On the other hand, if I included patients who experienced no effects and performed a statistical analysis, the statement would be more objective. However, without proper laboratory analysis, it would still be quite vague.

- Even if such a claim came from a physician, it would still constitute anecdotal evidence and likely represent a logical fallacy known as an argument from authority (argumentum ad verecundiam).

- The claim confuses correlation with causation, and vice versa. Just because two events occur simultaneously does not mean that the first is the cause of the second. As mentioned earlier, to determine whether the claim has merit and to apply the theory of probabilities effectively in future cases, one must gather relevant factual data for comparison. This brings us to the following point:

- Too often, factual data exists showing how and in what ways something could be dangerous. However, when a person holds a strong confirmation bias toward a pseudoscientific claim and receives support from a physician who reinforces that bias, it becomes nearly impossible to change their mind. What we typically observe is the selective use of data and the misinterpretation of results in ways that conform to the individual’s bias

A few more examples:

The issue of plastic pollution is a matter of grave concern, and it’s undeniable that human activities have significantly contributed to polluting and littering our planet. However, it’s important to recognize that ongoing research continues to reveal nature’s remarkable ability to adapt and respond to these environmental challenges within the broader context of evolution. While some may argue that pollution is destroying nature, others hold opposing views. This reflects the problem with common sense: it often produces subjective claims that conflict with one another and frequently diverge from scientific evidence.

Critical thinkers in this field approach the issue more factually, often concluding that human activities are, in fact, harming nature. However, a scientifically literate individual would consider not only the immediate damage but also long-term evolutionary dynamics, asking whether we truly possess the ability to destroy nature or life on the planet as a whole. What does this imply? When envisioning the future, humans often struggle to think beyond their immediate surroundings and the familiar timescales of their existence. We are creatures limited by our perceptions, frequently focusing on short-term planning and present-day concerns. Given the complexities of predicting far-future events, it becomes clear that our ability to plan effectively for the long term is limited. This is evident in our environmental track record, which highlights gaps in our foresight and emphasizes the need for improved sustainable decision-making.

Preconceptions about the issue also significantly shape our thought process. A person with a strong scientific background, for instance, wouldn’t rigidly adhere to preconceived notions about our impact on pollution. They would acknowledge our undeniable role in environmental changes but approach the problem more holistically, factoring in long-term evolutionary possibilities and keeping an open mind to future research. For instance, it’s possible to hypothesize the emergence of microscopic life forms capable of digesting plastics or oils, inspired by known bacteria like Alcanivorax borkumensis, which can metabolize hydrocarbons. Our attempts to “pollute” the environment could inadvertently trigger natural adaptations in microbial species, potentially incorporating our waste into their ecosystems.

Science communicator Anton Petrov [7] has explored how human interference is driving fascinating evolutionary changes, both microscopic and macroscopic. One particularly intriguing example is the adaptation of microorganisms that have begun to use plastic for various purposes, demonstrating resilience in an ever-changing world. [8] Imagine a scenario where plastic-eating bacteria proliferate, consuming all the plastic in their path.

While we have the power to shape Earth’s ecosystems, it’s essential to understand that our influence is largely confined to the current biotope that sustains us and other life forms. We may unintentionally disrupt this delicate balance, but it’s important to remember that the planet itself is resilient and capable of enduring. Our focus should therefore be on protecting and preserving the biotope necessary for our own survival and the continuation of life as we know it. Despite our concerns for the environment, it’s disheartening to see that we often fail to fully embrace sustainable practices. We struggle to align our modern lifestyles with renewable solutions, and our motivations for creating a healthier environment seem to be largely driven by immediate needs. This paradox is evident in how we advocate for climate action while continuing to consume products with large carbon footprints from distant regions. This behavior highlights a certain hypocrisy, which must be addressed openly. Acknowledging our shortcomings and our contribution to environmental challenges is a crucial first step.

It’s also important to recognize that, even in the event of a catastrophic incident, the Earth possesses an inherent ability to stabilize and regenerate over time. Nature is relentless and will persist, even if humanity is wiped from the planet. A new era would arise, free from our destructive tendencies. While our extinction would have devastating consequences for many species that depend on the current ecosystem, it would not mean the end of life itself. [9]

Gaining a clear understanding of the details mentioned above will provide valuable insights into the essence of scientific literacy. It will also help distinguish between common sense, critical thinking, and the essential concept of scientific literacy itself. Scientific literacy is crucial for shaping our thought processes; individuals who lack it may struggle to think objectively. Even those who demonstrate strong critical thinking skills in one area may inadvertently make scientifically inaccurate claims in another.

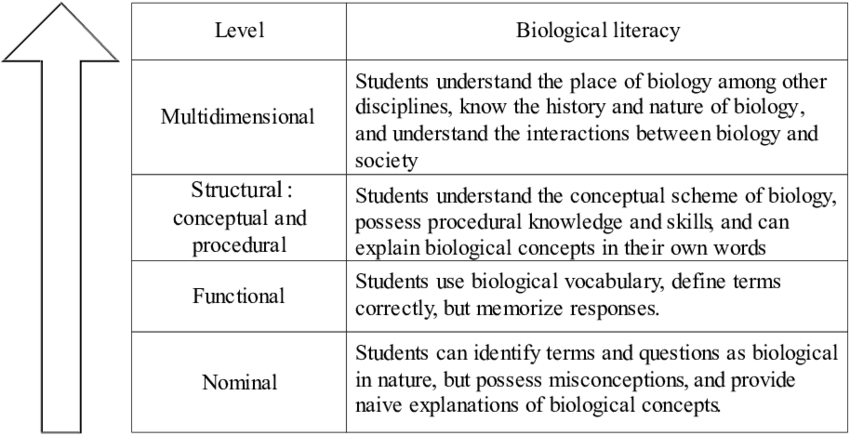

The accompanying datasheets offer a comprehensive overview of the functional and practical aspects of scientific literacy. These resources aim to illuminate the varying levels of scientific competency and understanding.

Source: Birzina, Rita. (2011). Biology students’ comprehension of learning as a development of their biological literacy.

Source: Impey, Chris. (2013). Science Literacy of Undergraduates in the United States. Organizations, People and Strategies in Astronomy Vol. 2. 353-364.

“I hate when people confuse education with intelligence; you can have a bachelor’s degree and still be an idiot.” – Elon Musk (Sadly, although his quote may be true, at this moment Musk himself has become an idiot.)

Many people are susceptible to unscientific ways of thinking for various reasons. Even the most rational individuals may unknowingly commit logical fallacies [10] on a daily basis. While this is normal, it is crucial to distinguish between simply being wrong and being confidently ignorant about incorrect conclusions, especially regarding topics where one lacks formal education and is scientifically illiterate. Moreover, even those with formal education are not immune to logical errors and scientific misconceptions. Passionate reading about a subject does not guarantee an understanding of scientific general framework, leaving individuals vulnerable to drawing incorrect conclusions or overlooking available research.

Numerous public figures believe they can engage in critical discussions on various topics. Many prioritize rhetorical strategies over substantive arguments. [11] A notable observation is that few participants in talk shows or debates acknowledge their own fallacies in real-time, underscoring the power of persuasive rhetoric, which often has a more immediate impact than well-structured arguments. While some individuals may be oblivious to critical analysis, many still rely on flawed premises in their arguments.

The ability to identify and challenge these fallacies, along with a commitment to self-reflection and constructive self-evaluation, is essential for fostering intellectual honesty and productive discourse. Mastering self-analysis is a challenging pursuit that requires not only intellectual capability but also dedication to personal growth. Even brilliant minds may experience lapses in real-time self-reflection, but true greatness lies in their capacity to recognize and rectify these fallacies. Labeling someone as an “idiot” for such lapses oversimplifies the issue; rather, it is our educational systems that often fail to instill a deep understanding of subjects like physics, chemistry, and biology. In this context, promoting scientific literacy is vital, as it empowers individuals to grasp fundamental principles about nature and appreciate the importance of scientific inquiry.

Today, we frequently observe individuals with a solid understanding of scientific principles mistakenly embracing or promoting pseudoscience. This is particularly troubling when it involves those who have received comprehensive education and should know better. Instead of using their expertise to educate others, they fall into demagoguery and spread misguided information, fostering a form of scientific illiteracy that hinders societal progress. Those who rely solely on common sense often become the most susceptible to these narratives.

Even individuals grounded in core sciences can be drawn to “woo” [12] and “new age” [13] movements. This trend points to a concerning gap in science communication within our educational systems. The proliferation of unfounded claims is often fueled by self-styled “New Age gurus” or motivational speakers. [14] The relationship between the body and mind has been particularly affected, especially in the wake of the ongoing pandemic. This issue spans various scientific disciplines, leaving none untouched by its influence. Alarmingly, some “well-educated” [15] public figures, including esteemed professors [16] and Nobel Prize laureates, continue to promote unscientific and unsubstantiated ideas.

Should All Highly Educated People Be Considered Scientifically Literate?

This question is significant and warrants a clear response: the answer is a definitive “No.” Here’s the reasoning behind this conclusion: individuals, including scientists and scholars, are influenced by their personal worldviews, though the degree of this influence can vary. In most cases, these personal beliefs do not interfere with their professional decision-making processes. For example, when seeking medical assistance, patients typically do not inquire about a physician’s political or philosophical affiliations, as such matters are generally considered irrelevant to the provision of medical care. However, issues arise when healthcare professionals intertwine public health matters with political views or adopt unscientific practices. In these situations, their inclination to incorporate pseudoscientific viewpoints into their diagnostic procedures may emerge. Consequently, any claims or diagnoses made without reliance on established scientific consensus should be viewed as speculative and potentially driven by demagoguery. Academic qualifications, regardless of discipline, do not automatically eliminate deeply ingrained patterns of irrational thinking. Even those with rigorous scientific training may interpret their discoveries through the lens of their ideological beliefs. This phenomenon is not limited to any specific profession; lawyers, physicians, historians, and individuals from various backgrounds can still endorse unjust practices, unwarranted belief in homeopathy, or engage in historical revisionism. Unfortunately, susceptibility to pseudoscience can persist despite years of education and exposure to reliable information. When combined with a general aversion to authority, these susceptibilities can lead to far-reaching consequences. Faced with such situations, individuals often selectively choose [17] and highlight specific data that align with their viewpoints, using it as a persuasive tool. This cherry-picking phenomenon is more common than we might realize, occurring in our own lives and the broader context around us. An illustrative example is when someone intentionally selects studies that support their stance while disregarding a much larger body of scientific facts that contradict it, thus reinforcing their confirmation bias.

In instances like this, we must firmly assert, “The scientific method does not operate in this manner! [18] One must evaluate and utilize the entirety of a study or refrain from distorting its findings.” Furthermore, to achieve the status of impartial scientific truth, a study must undergo rigorous peer review. Until such validation is obtained, we can only discuss inclinations or hypotheses tentatively, exercising caution in public discourse to prevent misinterpretations. Unfortunately, a lack of understanding surrounding the scientific process perpetuates widespread misconceptions, necessitating the dissemination of accurate information.

Science is often perceived by the public as a dynamic and evolving discipline, leading to the belief that scientific solutions to ongoing problems are frequently revised and, thus, unreliable. However, while scientific understanding can evolve, it is grounded in rigorous methodology and critical thinking. Therefore, it is important to approach scientific findings with careful consideration, as they provide valuable insights into our world. In the context of the ongoing pandemic, it is imperative to rely on accurate, peer-reviewed studies when discussing important matters such as vaccines. Unfortunately, there have been instances where preliminary research has been misused and misinterpreted by individuals claiming to be physicians or scientists, resulting in the spread of pseudoscientific arguments against vaccination. It is essential to approach such claims with skepticism and seek information from credible sources.

Science is neither inconsistent nor ambiguous in its statements; it adheres to a rigorous process of formulating hypotheses based on acquired data and established laws of nature. However, science is always open to investigating relevant issues. If a hypothesis is found untenable based on new evidence, it is adjusted or refined accordingly. This is the unwavering essence of scientific inquiry. While it may be tempting for some to adopt a contrarian stance, we must not overlook the concerning rise of anti-scientific sentiments in society. Accepting any bold and unchecked statement, including my own, without thoughtful examination would be a misguided approach. I (naively) believe that humanity’s capacity for discerning plausible scenarios from improbable ones will prevail, along with our pursuit of expanding collective knowledge grounded in sound reasoning, evidence, and a commitment to steering clear of superstition and debunked assumptions.

And again: Developing a scientifically literate way of thinking is not confined to experts or those with advanced qualifications; it is a fundamental skill that should be nurtured in elementary and high school education. While higher education can enhance critical thinking within specific fields, true scientific literacy extends beyond specialized knowledge. It empowers individuals to understand the role of science in society and to confidently apply scientific thinking in their daily lives.

How to Identify a Scientifically Literate and Ethical Scientist or Expert

To recognize a genuine and ethical scientist or scholar, it is essential to establish fundamental criteria. These criteria serve as reliable benchmarks for identifying individuals who truly embody the principles of scientific integrity and scholarship. Meeting all of these criteria is crucial, as the absence of any one may undermine the credibility and integrity of a purported scientist or scholar. Here are the key criteria to consider:

- A true scientist, scholar, or expert refrains from participating in public discourse about proposed claims until a thorough investigation and analysis have been conducted.

In the scientific community, it is essential for researchers to seek input and feedback from their peers. Peer review plays a crucial role in validating and refining scientific knowledge before it is published.

- It is essential to support any assertions with verifiable evidence, such as rigorous calculations, empirical tests, or peer-reviewed scientific data.

This can be summarized by Carl Sagan’s words: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” This is where many formally recognized scientists—and those who accept their claims—often fall short.

- As a logical consequence of the first point (I know I sound like a Vulcan), one should never rely on public support for claims after they have been proven false.

One discusses and writes about a topic with laymen after their claims have been challenged during the peer-review process, with the intention of attracting new ideologically biased followers and gaining momentum.

- One should never attempt to present a non-factual claim as a scientific truth, especially not in a conjunctive manner, and particularly before the claim has undergone scientific analysis.

In this scenario, a so-called “scientist” typically compiles these so-called “truths” into an esoteric book. To someone lacking scientific knowledge, these ideas may seem highly logical and comprehensible, leading them to accept the information as “valid science.” However, these writings often consist of simplistic rhetoric and nonsensical claims. While some thought-provoking questions may emerge, the overall content is largely filled with unfounded assertions and erroneous conjectures. Amid this pandemic, a surge of what can only be termed “weed literature” has emerged. Its authors boldly accuse legitimate scientists, who are earnestly investigating the virus and the critical issues we face, of being part of a sinister conspiracy. These accusations are sweeping, suggesting a plot to undermine our fundamental rights and more. Strikingly, these same authors, lacking substantial laboratory research, claim to possess irrefutable data and evidence. Yet their proposed solutions are glaringly inadequate, advocating for the unchecked spread of the pandemic. Historical parallels can indeed be drawn from past pandemics, which is fascinating; these authors seem to have unraveled the mysteries of the universe without ever stepping foot in a laboratory. Ironically, the dedicated scientists who spend countless hours in such facilities are unjustly accused of dishonesty and exaggeration. This paradox is nothing short of intriguing!

One notable example is religious organizations that promote Intelligent Design as a scientific theory, with the Discovery Institute being the most prominent in Western cultures. Their “Godfather,” Stephen Meyer, has authored several books that present pseudoscientific content on this topic.

- Starting an argument by highlighting one’s credentials as a scientist or scholar, or by emphasizing multiple titles as a measure of seriousness, is not a valid approach. [19]

This text describes a classic argumentative fallacy known as argumentum ad verecundiam, or an appeal to authority. Any claims made in this context can be easily dismissed because, even if they present some potentially valuable points, they often lack self-reflection and are rife with subtle argumentative inconsistencies..[20]

The distinction also lies in the quality of education and the proficiency of the instructors. Many new students and aspiring academics may grapple with cognitive dissonance, confirmation bias, and a tendency toward uncritical thinking.[21]

Moreover, it is undeniable that pseudoscientific reasoning significantly impacts how certain scholars interpret natural phenomena. Occasionally, individuals in positions of power may base their decisions on ideological preferences rather than scientific evidence. Even those with a fundamental understanding of core scientific principles may find it challenging to identify fallacious and manipulative rhetoric. In such cases, pseudoscientific ideas can seem remarkably persuasive and plausible. [22] Therefore, it is crucial to have a framework in place to identify not only scientists who may be engaging in unethical practices or lack scientific literacy but also to critically evaluate any unfounded assertions they may make. In this context, Michael Shermer has introduced a valuable resource known as the “Baloney Detection Kit,” which provides practical tools for discerning and debunking pseudoscientific claims. You can learn more about it here: Baloney Detection Kit.

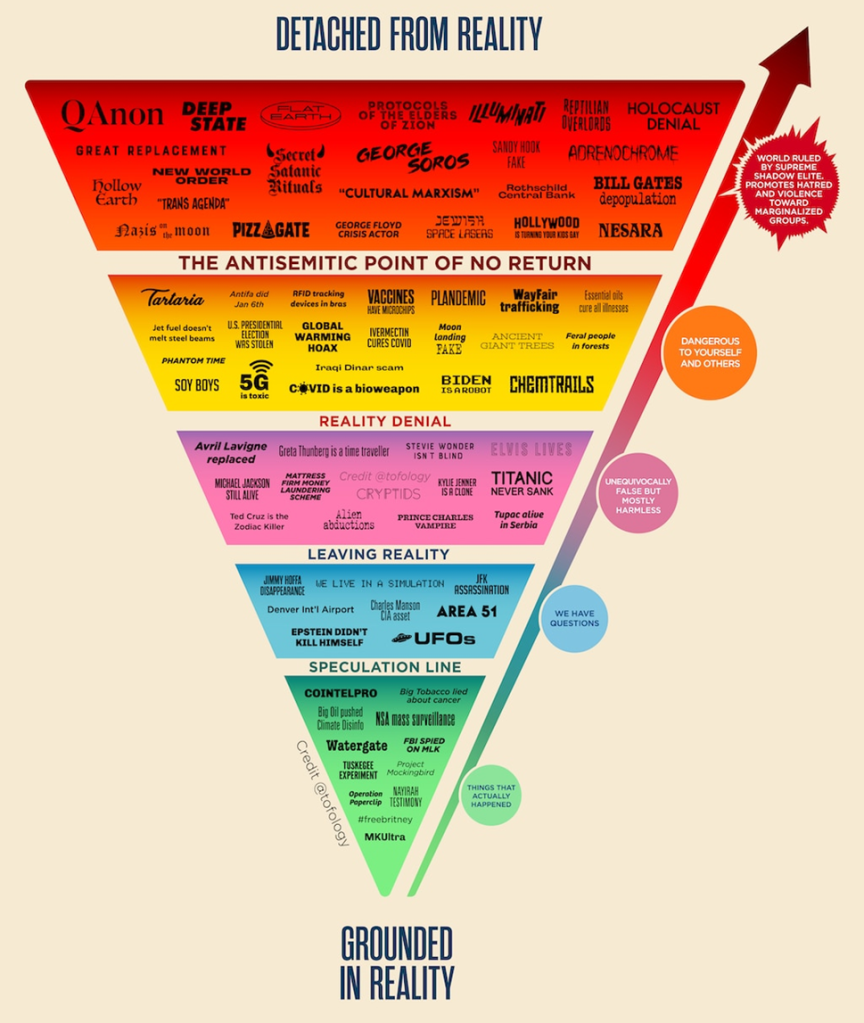

A following graphic, conspiracy chart 2021 [23], shows the steps of cognitive dissonance in respect to specific topic:

A Special Inquiry for Social Scholars: The Challenge of Scientific Literacy

Social scholars often find themselves in a concerning position regarding scientific literacy. Their understanding of this concept tends to be inadequate. Proficiency in one area of social analysis does not even ensure scientific literacy across all social disciplines. It is essential to recognize a fundamental aspect of this issue: scholars in the social sciences typically analyze phenomena through their ideological lenses and personal values. This perspective leads them to ask “why” questions, exploring underlying motivations and philosophical implications. In contrast, those with a strong background in the natural sciences focus on “how” questions, prioritizing an understanding of the mechanisms and processes governing various phenomena, often without ideological constraints, although some natural scientists may be not immune to ideological confirmation bias and cognitive dissonance, which can influence their evaluation of specific claims within their fields. A strong attachment to particular worldviews can increase susceptibility to argumentative fallacies, especially in areas where ideological orientation is not necessary. For example, grasping the complex concepts of how the universe can arise from nothing is an immense challenge that demands advanced mathematical skills or a thorough understanding of quantum mechanics. While social scholars are highly knowledgeable in their fields, they typically lack knowledge in these areas. As a result, their interpretations often carry ideological undertones, reflecting theistic, deistic, or pantheistic perspectives. A captivating analogy by the esteemed physicist Stephen Hawking aptly illustrates the idea of nothingness: “To help you get your head around this weird but crucial concept, let me draw on a simple analogy. Imagine a man wants to build a hill on a flat piece of land. The hill represents the universe. To create this hill, he digs a hole in the ground and uses that soil to form the hill. However, he’s not just making a hill; he’s also creating a hole, effectively crafting a negative version of the hill. The soil from the hole has now become the hill, so everything balances out. When the Big Bang produced a massive amount of positive energy, it simultaneously generated an equal amount of negative energy, resulting in a net sum of zero. This is another law of nature. So, where is all this negative energy today? It resides in the third ingredient of our cosmic cookbook: space. … I’ll admit that, unless mathematics is your thing, this is hard to grasp, but it’s true.”[24]

In the following sections, I will present two main cases as examples of scientific illiteracy and anti-science sentiment.

Next part: THE CLAIM: “SPACE EXPLORATION IS NOT IMPORTANT” as a showcase of science illiteracy – (Pt.2/3)

[1] Our history recollects many pandemic events and this one is surely not the last one.

[2] Like in the well-known comedy “Idiocracy”.

[3] A basic level of understanding requires at least a solid grasp of elementary and high school education in physics, chemistry, and biology. Additionally, it involves the ability to distinguish between plausible and implausible assertions, evaluate probabilities, make comparisons, and formulate logically connected follow-up questions.

[4] According to one of many possible definitions, an amateur scientist is: “One who is a scientific investigator as a pastime rather than a profession.” Body (madscitech.org); (re)acquired on 01.12.2021

[5] Stephen Hawking: A brief history of time (New York, Bentam books; 2017); p.18

[6] https://study.com/academy/lesson/scientific-literacy-definition-examples.html

[7] ANTON PETROV – MATH & SCIENCE TEACHER – Home (weebly.com); last time acquired 07.01.2021

[8] Surprising Ways How Life Is Adapting To Plastics On Planet Earth – YouTube; last time acquired 07.01.2021

[9] Great stand-up comedian and philosopher, George Carlin, has vividly and in funny way explained our role in nature (a part of the transcript I simply had to repost):

“See, I’m not one of these people who’s worried about everything. You got people like this around you? Countries full of them now: people walking around all day long, every minute of the day, worried… about everything! Worried about the air; worried about the water; worried about the soil; worried about insecticides, pesticides, food additives, carcinogens; worried about radon gas; worried about asbestos; worried about saving endangered species. Let me tell you about endangered species all right? Saving endangered species is just one more arrogant attempt by humans to control nature. It’s arrogant meddling; it’s what got us in trouble in the first place. Doesn’t anybody understand that? Interfering with nature. Over 90% – over, WAY over – 90% of all the species that have ever lived on this planet, ever lived, are gone! Pwwt! They’re extinct! We didn’t kill them all, they just disappeared. That’s what nature does. They disappear these days at the rate of 25 a day and I mean regardless of our behaviour. Irrespective of how we act on this planet, 25 species that were here today will be gone tomorrow. Let them go gracefully. Leave nature alone. Haven’t we done enough?

We’re so self-important, so self-important. Everybody’s gonna save something now: “Save the trees! Save the bees! Save the whales! Save those snails!” and the greatest arrogance of all: “Save the planet!” What?! Are these fucking people kidding me?! Save the planet?! We don’t even know how to take care of ourselves yet! We haven’t learned how to care for one another and we’re gonna save the fucking planet?! I’m getting tired of that shit! I’m getting tired of that shit! I’m tired of fucking Earth Day! I’m tired of these self-righteous environmentalists; these white, bourgeois liberals who think the only thing wrong with this country is there aren’t enough bicycle paths! People trying to make the world safe for their Volvo’s! Besides, environmentalists don’t give a shit about the planet. They don’t care about the planet; not in the abstract they don’t. You know what they’re interested in? A clean place to live; their own habitat. They’re worried that someday in the future, they might be personally inconvenienced. Narrow, unenlightened self-interest doesn’t impress me.

Besides, there is nothing wrong with the planet… nothing wrong with the planet. The planet is fine… the people are fucked! Difference! The planet is fine! Compared to the people, THE PLANET IS DOING GREAT: Been here four and a half billion years! Do you ever think about the arithmetic? The planet has been here four and a half billion years, we’ve been here what? 100,000? Maybe 200,000? And we’ve only been engaged in heavy industry for a little over 200 years. 200 years versus four and a half billion and we have the conceit to think that somehow, we’re a threat? That somehow, we’re going to put in jeopardy this beautiful little blue-green ball that’s just a-floatin’ around the sun? The planet has been through a lot worse than us. Been through all kinds of things worse than us: been through earthquakes, volcanoes, plate tectonics, continental drifts, solar flares, sunspots, magnetic storms, the magnetic reversal of the poles, hundreds of thousands of years of bombardment by comets and asteroids and meteors, worldwide floods, tidal waves, worldwide fires, erosion, cosmic rays, recurring ice ages, and we think some plastic bags and aluminum cans are going to make a difference?

The planet isn’t going anywhere… we are! We’re going away! Pack your shit folks! We’re going away and we won’t leave much of a trace either, thank God for that… maybe a little styrofoam… maybe… little styrofoam. The planet will be here, we’ll be long gone; just another failed mutation; just another closed-end biological mistake; an evolutionary cul-de-sac. The planet will shake us off like a bad case of fleas, a surface nuisance. You wanna know how the planet’s doing? Ask those people in Pompeii who are frozen into position from volcanic ash how the planet’s doing. Wanna know if the planet’s all right? Ask those people in Mexico City or Armenia or a hundred other places buried under thousands of tons of earthquake rubble if they feel like a threat to the planet this week. How about those people in Kilauea, Hawaii who build their homes right next to an active volcano and then wonder why they have lava in the living room?

The planet will be here for a long, long, LONG time after we’re gone and it will heal itself, it will cleanse itself cause that’s what it does. It’s a self-correcting system. The air and the water will recover, the earth will be renewed, and if it’s true that plastic is not degradable, well, the planet will simply incorporate plastic into a new paradigm: The Earth plus Plastic. The Earth doesn’t share our prejudice towards plastic. Plastic came out of the Earth! The Earth probably sees plastic as just another one of its children. Could be the only reason the Earth allowed us to be spawned from it in the first place: it wanted plastic for itself, didn’t know how to make it, needed us. Could be the answer to our age-old philosophical question: “Why are we here?” PLASTIC!!! ASSHOLES!!!”; George Carlin: Saving the Planet – Full Transcript – Scraps from the loft

[10] Those with any formal debating experience will understand the point I am making. For those without such experience, I recommend visiting the following link, where you can find informative resources about debate, as well as a comprehensive list of logical fallacies: Glen Whitman’s Debate Page (csun.edu); last time acquired 05.12.2021

[11] An article about fallacious argumentation: A Populist Writer and Critic – How Intellectual Bogus Leader Richard D. Precht Misleads Us Once Again with Nonsensical Arguments, this Time on Corona | Lars Jaeger; last time acquired 05.12.2021

[12] https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Woo; last time acquired 08.12.2021

[13] https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/New_Age; last time acquired 08.12.2021

[14] Just to name a few:

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Oprah_Winfrey ;

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Eckhart_Tolle ;

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/David_Icke ;

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Gwyneth_Paltrow ;

all last time acquired 08.12.2021

[15] Just to name a few:

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Bruce_Lipton ;

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Deepak_Chopra ;

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Jordan_Peterson ;

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Andrew_Wakefield ;

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Vandana_Shiva;

Dr. Steven Gundry | Goop (is part of the https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Gwyneth_Paltrow group)

all last time acquired 08.12.2021

[16] E.g. Sucharit Bhakdi, Geert Vanden Bossche; More about it here:

English Version: Scientists opposing Corona measures – The Line between Healthy Scientific Scepticism and providing support to the absurd QAnon movement | Lars Jaeger; ; last time acquired 08.12.2021

German Version: Wissenschaftler als Gegner von Corona-Massnahmen – Der Grat zwischen gesunder wissenschaftlicher Skepsis und Unterstützung der absurden Querdenker-Bewegung | Lars Jaeger; last time acquired 08.12.2021; here as well; Famous Doctors and Their Dangerous Disinformation (digicomnet.org); ; last time acquired 08.12.2021

[17] Cherry-picking is one of the most prominent and most used argumentative fallacy.

[18] In this respect I would strongly recommend a following interview with Neil DeGrasse Tyson: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/w3ct1n6t or https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qIXPj1TFz-g; last time acquired 30.12.2021

[19] In several European countries, academic titles carry significant weight, representing both seriousness and social status. This cultural phenomenon can be traced back to the historical contexts of monarchy and aristocracy. As these societies transitioned to republics, academic titles began to replace old aristocratic titles, acquiring considerable social importance. In some cases, the pursuit of multiple titles has become more of a cultural trend than a genuine quest for knowledge and scientific enlightenment. Consequently, it is not uncommon to encounter individuals with numerous title abbreviations, such as MMag. and DDDr., indicating multiple master’s and doctoral degrees. While this trend has given rise to “title careerists,” it is essential to recognize that many academics genuinely possess scientific knowledge and expertise. However, distinguishing between the two can be challenging, as some title careerists hold influential positions and are even recognized as national intellectuals, despite promoting pseudoscientific ideas.

[20] E.g.: Jordan Peterson is a highly influential figure who frequently employs the argumentum ad verecundiam fallacy in his discourse. Despite any shortcomings, he has cultivated a substantial following, largely due to his reputation as a skilled rhetorician who appears to have all the answers. In a world where time is a precious commodity, many individuals find comfort in turning to charismatic figures like Peterson, who claim to have unraveled complex subjects. However, it is essential to recognize that these individuals often package their own biases as truth and secret knowledge, which can relieve the audience of the responsibility to engage in critical thinking.

While some may hastily label Peterson as a far-right figure, he actually operates within the center-right spectrum, expressing a nostalgic yearning for a bygone era. This nostalgia is a common trait in conservative ideologies, although it can also be found in certain left-wing circles. Through his public appearances and interviews, Peterson has articulated his admiration for Dostoevsky, an unwavering belief in the superiority of capitalism, and the view that hierarchies are inherently rooted in evolution. He has also made controversial remarks about women’s preferences, their suitability for leadership roles due to inherent maternal instincts, and the intelligence of people of color. It is remarkable how he displays such a superficial understanding of philosophy and history. One cannot help but question the legitimacy of his criticisms, particularly regarding postmodernism. His casual use of terms like “postmodern neomarxism” reflects a lack of intellectual depth. It is baffling how he expects his audience to engage with such jargon when he himself seems to struggle with its meanings. Regarding his notion of truth, it appears to be little more than a weak attempt to pander to his audience’s biases rather than providing meaningful or objective insights. Peterson’s views have often been criticized for their lack of rationality and honesty. His efforts to reconcile his religious beliefs with reality have led to contradictory worldviews. Despite presenting himself as an authority on various subjects, Peterson’s epistemic views are regressive and hinder intellectual progress.

[21] Caused by any ideological influence (mostly, religious type spiritualism; old or new) or by misunderstanding of natural processes, where the level of available skepticism does not allow questions about own convictions and knowledge.

[22] E.g. The damage caused by Andrew Wakefield’s claim that vaccines cause autism is ongoing. His assertion has also revitalized the anti-vaccination movement, which hampers global vaccination efforts in numerous regions.

[23] https://conspiracychart.com/

[24] Stephen Hawking: Brief answers to the big questions (London, John Murray (publishers); 2020); pp.32-33.

One thought on “SCIENTIFIC (IL)LITERACY AND ITS SOCIAL CONSENQUENCES (Pt.1/3) Edition 2024”

Comments are closed.