DISCLAIMER

In early 2022, I published a three-part series related to the topic above. Writing the articles took several months before they were ready for publication. I won’t delete these original texts, as I consider them the first edition. However, since then, certain changes have allowed me to update the content with new information. First, the emergence of more reliable AI language tools has helped me improve grammar, syntax, and flow, while preserving the original ideas and creativity. Some parts of the original text were vague or difficult to understand and required revision. Second, new data has surfaced, further supporting the points I made back then in a clearer and more impactful way. Lastly, the topic itself has gained significant traction in the post-pandemic world, where we are seeing an overwhelming spread of pseudoscientific and anti-intellectual content.

Previous part: INTRODUCTION – (Pt.1/3)

THE CLAIM: “SPACE EXPLORATION IS NOT IMPORTANT” as a showcase of science illiteracy

Space exploration is an immensely significant and fascinating subject that I am deeply passionate about. In the previous paragraph, I briefly addressed the issue of scientific illiteracy and its relevance to pandemics. To examine this further, I will dedicate Part 3 of this discussion to exploring the consequences of scientific illiteracy in that specific context. This topic demands attention, as it illuminates the current state of society’s understanding and valuation of scientific knowledge.

“We were wanderers from the beginning”- Carl Sagan[1]

When reflecting on a scientifically informed mindset, it is striking to observe the public’s misguided perspectives on space exploration and the potential colonization of other planets [2]. I firmly believe that viewing space exploration as “time and money thrown away” exemplifies such misunderstanding. Consequently, I feel compelled to revisit and expand upon my earlier article regarding the science illiteracy that afflicts this particular domain of human endeavor. By delving into the importance of space exploration, and of exploration more broadly, I aim to demonstrate its undeniable value. Space exploration has faced criticism, even from well-educated individuals, particularly in the social sciences. It is troubling that some within my own academic community (law scholars) have voiced objections to various aspects of space exploration without fully considering the long-term consequences that might follow the abandonment of scientific inquiry in this domain. The widespread underappreciation for fundamental sciences, and for the far-reaching implications of scientific research and exploration, impairs our collective understanding of the transformative advancements made possible by space programs. These programs have not only enhanced daily life but have also played a critical role in addressing environmental degradation, preserving biodiversity, and confronting global challenges. Their legacy includes groundbreaking medical research, strategies for minimizing human impact on the environment, the development of cutting-edge technologies, practical and sustainable solutions, a deeper understanding of Earth’s climate, and the emergence of entirely new job markets. These contributions have generated insights and innovations so embedded in our lives that they are often taken for granted. In fields such as space exploration, medicine, engineering, biotechnology, and oceanography, it is disheartening to witness educated individuals, particularly in the social sciences, employing unscientific and irrational reasoning when discussing the efforts within these domains. Such attitudes can obstruct progress and stifle the advancement of knowledge in disciplines vital to our collective future.

Why colonize other planets instead of saving this one first?

In the spirit of evolutionary thought, the survival of every living being is deeply intertwined with the imperative to explore and acquire new habitats. The ability to adapt to constant change is the key determinant of continued existence. As discussed previously, the sobering example of marine life contending with the omnipresence of plastic serves as a poignant reminder of the necessity of adaptation in the face of adversity. In the dynamic web of life, both animals and plants are in a constant struggle to adjust to environmental shifts. This process is driven by natural forces, such as the movement of tectonic plates. A species’ ability to find new habitats where it can thrive and swiftly occupy vacant ecological niches ultimately determines its survival. Understanding this principle is essential to grasp the mechanisms of evolutionary dynamics. Humans, as members of the animal kingdom, possess a remarkable instinct for survival. This deeply ingrained biological drive continues to shape our fascination with space exploration. Like all other species, we respond to natural or self-induced threats to our existence. What sets us apart is our capacity to perceive and understand the world at a profound cognitive level. From this perspective, our pursuit of space exploration becomes not just ambition but a testament to the depth of human curiosity and ingenuity. As the most cognitively advanced species on Earth, we possess the unique ability to comprehend our nature and envision our future. This capacity empowers us to embrace the principles of evolution and adapt proactively to an ever-changing world. Critics of space exploration must first understand these foundations to appreciate how it reflects our innate survival instincts and our proactive stance against potential extinction events. Harnessing the full potential of our cognitive abilities extends far beyond reproduction or idyllic fantasies of self-sufficient living. Some claim modern technology is unnecessary and that a handful of plants and seeds are sufficient for a sustainable, fulfilling existence. While the vision of a self-sustaining society is attractive, the reality is far more complex. With a global population approaching 8 billion [3], reverting to a pre-industrial, hunter-gatherer lifestyle is not a viable option. Our technological progress has delivered immense benefits and possibilities that must not be overlooked. Instead of regressing, we should explore new economic paradigms that shift from consumerism to sustainable, anti-consumerist models. A mindset focused on protecting natural habitats and pursuing space exploration offers promising prospects. Exploring the universe and pushing past Earthly boundaries exemplifies humanity’s potential and serves as a catalyst for advancements in chemistry, biology, and other fields, helping us address urgent environmental and social issues here on Earth. Our journey into space is driven by an insatiable pursuit of innovation and sustainability. In this era of scientific exploration, the potential to solve pressing global problems becomes increasingly apparent. Science has already provided countless solutions and insights, though implementation can be challenging. We must also correct the misconception that societal problems stem solely from incompetent or corrupt governments or industries. While these entities are not without fault, they also provide essential infrastructure, services, and products that mitigate numerous challenges and evolutionary mismatches. Without such institutions, organizing billions of people in a peaceful and functional society would likely collapse. Modern scientific endeavors, whether in space, geology, or medicine, require structured, cooperative efforts. This is where scientific illiteracy becomes most apparent. Instead of recognizing the necessity of organized institutions, people who irrationally distrust authority often overlook the substantial benefits these structures offer.

Institutions are composed of individuals, each with personal agendas, but this does not mean dangerous products or policies are automatically implemented at the whim of a CEO. One of the core strengths of institutions and oversight is their ability to manage, evaluate, and disseminate knowledge. Many offer open access to a wealth of scientific literature. In the case of space exploration, serious engagement with scientific research reveals how advances in space technologies can contribute meaningfully to solutions for energy use, sustainable living, and more. Our current crises are not the product of shadowy conspiracies by industries like pharmaceuticals or fossil fuels. They are more often the result of human nature, our tendency to ignore inconvenient truths. When leaders in these sectors operate within cognitive bubbles and reject the scientific consensus on issues like climate change, their behavior reflects denial and inertia, not grand conspiracies. They are human too. In a media landscape tailored to reinforce existing beliefs, confirmational biases thrive. Outlets deliver easy answers that feel true but lack rigorous scientific backing. This dynamic fosters suspicion toward institutions, regardless of their track record or integrity. Addressing complex problems by leaning on simplistic generalizations or avoiding research is intellectually lazy and logically flawed. Instead, we must engage deeply with empirical studies, particularly those examining how space exploration affects society. It’s remarkable and troubling when academics declare that space exploration is a “waste of money” or insist that “we must not venture into the unknown.” Such views reflect a lack of scientific literacy and an underappreciation of the value of fundamental research. Social sciences themselves owe much to the scientific advances in fields like astrophysics, chemistry, and biology, which provide the empirical foundation for serious societal analysis and development.

A long-term perspective introduces yet another dimension: the cosmic timescale. The universe is approximately 14 billion years old; the solar system, around 4.5 billion. The emergence of life, particularly intelligent life, requires vast stretches of time and favorable conditions. Conditions that the universe, through cataclysmic events, frequently destroys. Earth has already experienced five mass extinctions, with the Permian extinction 250 million years ago being the most devastating. Even the sun, our life-sustaining star, has a finite lifespan and will ultimately render Earth uninhabitable. Despite these immense timescales, we cannot afford complacency. Natural disasters and human-made ones can strike without warning. To ensure survival, we must act now. This includes developing planetary defense systems against asteroid impacts and building the capacity for off-world habitation. Waiting for future generations to solve these issues is reckless. The development of these capabilities may span decades or centuries—far beyond short-term political or economic cycles. Neglecting to act would squander the evolutionary gift of the human brain and leave us vulnerable to extinction, whether by external forces or by our own shortsightedness. Earth is a rare jewel in the cosmos, teeming with life. As the only known species capable of preserving and extending life beyond our planet, we bear the immense responsibility to do so. Our intellect shaped by the same evolutionary forces that govern all life offers the tools to ensure the continuity of life. One of the most effective ways to alleviate pressure on Earth’s fragile ecosystems is through space colonization. Technological progress toward viable interplanetary travel, including solutions for energy [4], food production, and resource conservation, is a crucial step in this direction. Expanding our industries beyond Earth is not merely about settling new planets, it represents a leap toward sustainable development on a cosmic scale.

I assume people will now say: “Oh, now we want to pollute another planet.” [This, by the way, is a reaction grounded in fallacious “common sense” reasoning.] The statement is flawed because it implies the existence of an already developed bio-environment on another celestial body. According to current scientific data, no such environment has been found, certainly not within our solar system. If there is nothing to pollute, how can one pollute it at all? We cannot seriously claim that we are polluting, for example, a star or the Moon. By one standard definition, “Pollution is the introduction of harmful materials into the environment. These harmful materials are called pollutants. Pollutants can be natural, such as volcanic ash. They can also be created by human activity, such as trash or runoff produced by factories. Pollutants damage the quality of air, water, and land.“[5] This does not mean we are incapable of creating messes. Yes, we could litter and rather than claiming we would pollute, littering [6] would be the more accurate term. Yet littering would pose problems only for us. A sterile celestial object is indifferent to a few crashed satellites on its surface.

As we soar higher and higher, our relentless pursuit of innovation compels us to continually refine our technology and tools, forging a path toward greater efficiency and environmental sustainability. By meticulously enhancing each stage of the rocket-building process, we push the boundaries of technological advancement, testing and validating cutting-edge solutions in the unforgiving vacuum of space. Space exploration has profoundly influenced the development of technologies we now take for granted. Through sustained research and development, it has driven significant progress across multiple fields such as reducing overall energy consumption which has, in turn, benefited society at large. Without the continuous push and discoveries born of space programs, the timeline for refining and deploying new technologies would be substantially delayed. Less efficient tools and appliances would remain in circulation longer, exacerbating global energy demands, especially in tandem with population growth. Some folks argue we don’t need space programs to spark innovation. They claim we can achieve the same results right here on Earth. But let’s be honest, it’s not that simple. While we can attempt to simulate a gravity-free environment, it’s never quite equivalent to actually being in space. Moreover, maintaining such simulations would require constant energy input and intensive upkeep, making them costly and inefficient.[7] As a result, they’re hardly viable for large-scale development. To reap valuable by-products from major innovations, strong motivation and sustained investment are essential. Simulations can only go so far; they fall short in capturing the full spectrum of challenges and variables encountered in actual space environments. As mentioned, many tools and technologies ranging from safety systems to energy-efficient appliances have emerged directly from space exploration. These innovations have even helped to advance concepts like self-sufficiency.

The mere thought of venturing into the depths of space and colonizing celestial bodies is often clouded by fear and pessimism. Detractors frequently invoke the flawed analogy that history will inevitably repeat itself, drawing parallels to European colonization of the New World. But is it truly fair to assume that humanity is fated to replicate its past mistakes? Perhaps, but this remains a rather overstated accusation. A few points are worth considering here.

First, when it comes to migration and the search for resources, humans are simply following a deeply ingrained instinct shared by all living beings. Throughout history, our ancestors sought out fertile lands and abundant resources to survive, prosper, and assert dominance. Today is no different. With ever-expanding needs and desires, human exploration and migration to new territories is not only inevitable but intrinsic to our nature. This relentless pursuit has shaped our past and will continue to shape our future.

Second, it is important to recognize that Native tribes were not fundamentally different from Europeans in terms of social dynamics. Despite cultural and geographical distinctions, both were human societies exhibiting similar behavioral patterns shaped by their respective levels of social and technological development. For instance, archaeological evidence indicates that some Native tribes migrated across the ancient Beringian Strait approximately 13,000 years ago, entering what is now North America.[8] The nature of their interactions with their environment and each other remains an area of active research. While a romanticized view portrays these tribes as living in complete harmony, historical and anthropological evidence points to inter-tribal competition and conflict, which, like elsewhere in the world, were integral to survival and territorial claims. Native populations across all continents displayed varying degrees of aggression, long before European contact.

In many cases, European migrants arrived believing they were the first to inhabit the land, only to be surprised by the presence of Indigenous peoples. This mutual shock often bred fear, leading to inevitable conflicts and a strained relationship. European expansion had far-reaching consequences, including warfare and the spread of devastating diseases.[9] However, we must reject the simplistic narrative that Native Americans were inherently peaceful and in perfect balance with nature, while Europeans were singularly driven by a genocidal impulse. Such a binary view distorts a complex and multifaceted historical reality. Similarly, to claim that space exploration, particularly when led by Caucasian-European entities, is inherently destructive is a gross misreading of history.[10] Is it logical to conclude that all exploration must be viewed as harmful simply because some aspects of European colonial history had negative environmental impacts? Such reasoning is reductive and unfounded. Blaming one cultural group as the sole perpetrator of harm while idealizing others as blameless simplifies a complex tapestry of human behavior. Conflict, by its nature, often involves escalation from both sides. For example, once a conflict begins, retaliatory actions by the victim can be seized upon by aggressors to justify continued violence, thus perpetuating the cycle. The dynamics between the Spaniards and the Aztecs illustrate this well. Deep animosities, fueled by Aztec raids on Spanish settlements, during which captives were sometimes sacrificed, played a role in shaping Cortez’s brutal campaign, culminating in the destruction of Cholula. However, alongside warfare, the role of disease in decimating Indigenous populations cannot be overstated. The introduction of new pathogens had catastrophic consequences, often more deadly than direct conflict.

Some Indigenous societies built expansive urban centers that eventually collapsed under pressures familiar to any complex civilization: resource scarcity, internal strife, disease, environmental degradation, and natural disasters.[11] The Mayan civilization is a notable example. While prolonged drought played a significant role, their decline was the result of a convergence of factors: overpopulation, warfare, environmental mismanagement, shifting trade networks, and seismic activity. Crucially, these developments occurred centuries before European contact, highlighting that civilizational collapse is not solely a colonial phenomenon. The spread of diseases by Europeans was undeniably tragic, yet it is plausible that such diseases would have eventually reached the Americas through other forms of global contact. As observed today, isolated tribes lacking access to modern medicine still suffer devastating consequences from illnesses considered minor elsewhere. This underscores the point: historical injustices must be acknowledged, but arguments should rest on evidence, not assumptions or ideological overreach.

The preservation of nature and minimization of harm are vital goals, but we must also be grounded in scientific reality. The laws of thermodynamics remind us that some level of environmental impact is inevitable. No living organism can exist without altering its surroundings. Human activity, through biological needs and social structures, necessarily contributes to entropy. Striving to reduce our footprint is admirable, but the notion of total non-interference with nature is a utopian ideal, not a practical reality.

“The costs of such endeavors are too high in comparison to their effective usefulness!”

I must express my strong disagreement with a claim that frequently arises among social scholars, the notion that we are investing too much in space programs. As someone well-versed in the social sciences, I find it imperative to highlight the immense value that space exploration brings to our understanding of nature and our own existence. In fact, I would argue that space exploration offers insights far more profound than those produced by the combined efforts of many social science disciplines.

What is particularly disheartening is that such criticisms are rarely directed at fields like economics, political science, or law, which also receive substantial funding. Unlike some social scholars, I commend natural scientists for their intellectual humility and acknowledge the vast contributions they make to our collective knowledge. I would argue that space exploration, and the broader pursuit of understanding nature, is among the most effective scientific endeavors in advancing human well-being and in dispelling misconceptions about the world we inhabit.[12] It instills, unequivocally, a sense of reverence for the awe-inspiring marvels of the cosmos. As previously noted, the core sciences form the bedrock of knowledge production, pioneering discoveries that profoundly shape the foundations of all scholarly disciplines. Their contributions are indispensable to our evolving comprehension of reality. Consider, for example, the task of understanding how social group dynamics emerge, or what psychological conditions underpin criminal responsibility. To address such questions, we must first understand something about cognition, that is, the brain itself. In this regard, I propose a simplified chain of dependencies that illustrates the relationship between the sciences and the humanities:

We begin with a (particle) physicist whose pursuit of new discoveries necessitates the creation of more precise instruments. These tools and the accompanying breakthroughs may find applications in fields such as biochemistry and neuroscience, which then strive to uncover and explain the brain’s biochemical processes. Some of their findings may, in turn, prove crucial to questions of criminal accountability, helping to refine our understanding of individual decision-making. If psychology and psychiatry then integrate these scientific insights, paradigm-shifting advances may follow, changes that could reverberate through disciplines such as criminology, compelling them to reassess their foundational theories.

Each time a core scientific discovery illuminates something fundamental about our cognitive apparatus, scholarly disciplines are, so to speak, compelled to shift toward a new paradigm of human understanding. As previously suggested, these disciplines rarely produce such transformative discoveries independently.[13] I studied law, and I am acutely aware of this reality. That said, my intention is not to diminish the significance of scholarly disciplines in addressing specific areas of human concern. However, we must be honest about the fact that we, as social scholars, rely far more on the core sciences than they rely on us.

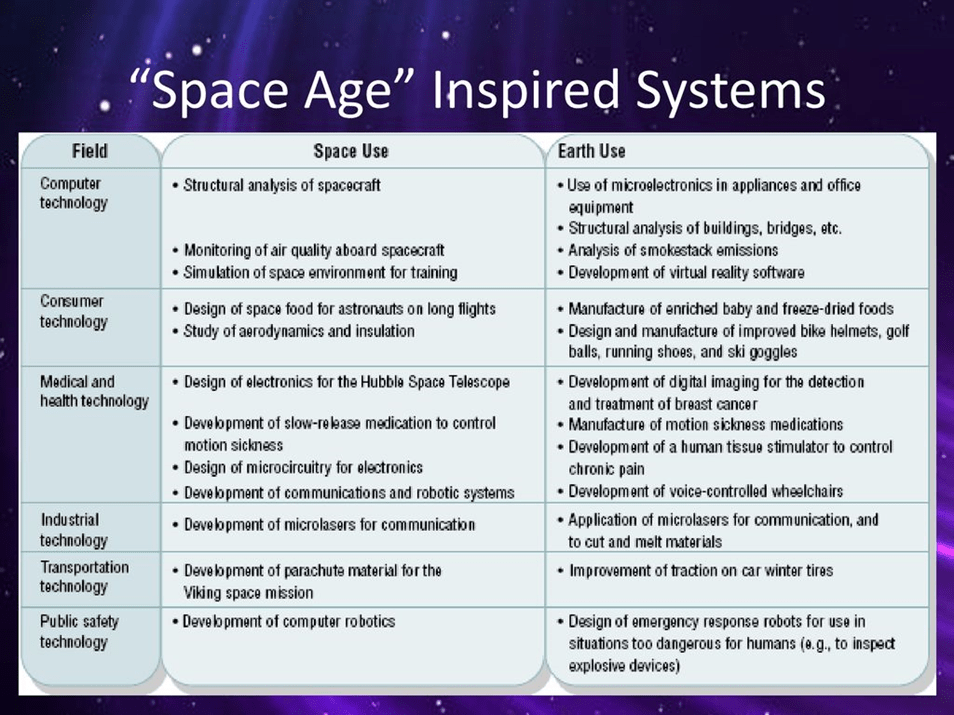

Returning to the benefits of space exploration: many of them are embedded in our daily lives in ways we often overlook. The list is too extensive to explore fully here, but a few examples are worth mentioning (see image below).[14]

Numerous space programs have consistently pushed the boundaries of human achievement. A remarkable example of this pioneering spirit is the successful launch of the James Webb Space Telescope [15]. This extraordinary endeavor drew on the collaboration of thousands of brilliant individuals, along with the vital contributions of small and medium-sized businesses. Over the course of a decade, the project took shape as a testament to human creativity and teamwork. Since the inception of space travel, each mission has not only created jobs but also driven the development of cutting-edge technologies. Few activities are as captivating or inspiring in times of peace as space exploration, for it propels collective progress and kindles the flame of human curiosity.

Pollution caused by space exploration is too high!

Well, this claim is quite easy to debunk. One could simply respond, “No, it is not too high.” I’ll try to make this as straightforward as possible. If we compare emissions per passenger between an average rocket and a Boeing 747, it’s clear that the rocket emits significantly more. However, the frequency of flights plays a far more important role.

According to calculations by Everyday Astronaut, in 2018 there were approximately 37.8 million commercial flights compared to just 114 orbital rocket launches. That’s 331,579 times more plane flights than rocket launches. Based on this, he concludes:

“…emissions from all commercial aviation in 2018 totaled 918,000,000 tonnes of CO₂. Compare that to the 22,780 tonnes from the aerospace industry in that same year, and we realize that you would have to fly 40,300 times more rockets per year to equal the output of airliners. That is 4,594,200 rocket launches a year, or 12,586 launches per day. And that’s assuming the same ratio of dirty solids, hypergolic, or kerolox rockets that we had in 2018, rather than the current trend toward cleaner methalox or hydrolox alternatives.

…

And now I think it’s time we put airliners into perspective, since we’ve been using them as the benchmark for CO₂ emissions. CO₂ emissions from the airline industry accounted for only 2.4% of global CO₂ emissions. So, in 2018, the global CO₂ output of rockets was just 0.0000059% of all CO₂ emissions. In other words, there are much bigger fish to fry. Worrying about the current CO₂ output of rockets, in comparison to other global contributors, is like focusing on a single leaf in a forest fire. There are far worse offenders we should be addressing.”[16]

So much for the claim that “rockets pollute too much.” I’ll rest my case here and strongly recommend reading the full article—it’s far better written than anything I could summarize here. It’s highly informative and serves as a great example of well-executed science communication on rocket science.

Exploration itself has nothing to do with altruism!

Here, I would like to begin with the following quote:

“Common rationales for exploring space include advancing scientific research, national prestige, uniting different nations, ensuring the future survival of humanity, and developing military and strategic advantages against other countries.”[17]

As the quote suggests, space exploration serves several monumental purposes, among them, uniting nations and ensuring the future survival of humanity. Unlike many other human enterprises, the quest for space has the rare power to unify us in a shared endeavor. While not all private space companies may fully embrace these noble ideals, such values remain intrinsic to the very spirit of exploration beyond our terrestrial sphere.[18] Like other scientific undertakings, space exploration is driven by the collective efforts of numerous dedicated scientists across various organizations. Their mission is oriented toward addressing the complex challenges humanity faces, both present and future. As I previously noted, space exploration yields numerous benefits. If we were to claim that only purely altruistic activities with perfect resource allocation are worthy of support, we would have to apply this logic consistently across all domains of research. Doing so would undermine even the most essential forms of social science. It is crucial, then, to acknowledge that much of scientific exploration is motivated not solely by utility but also by a spirit of altruism, solidarity, and intellectual curiosity. The fact that scientists are compensated or that their work can be misused for less noble ends does not nullify the sincerity of their motives. To argue otherwise would be fallacious.

Many brilliant minds have pursued knowledge out of a genuine desire to serve humanity and expand our collective potential. Their passion for discovery has left an indelible mark on the institutions they served. Consider the esteemed astrophysicist Carl Sagan: his work on NASA’s Voyager missions not only deepened our understanding of the cosmos but also instilled a renewed appreciation for Earth’s fragility. His famous speech, Pale Blue Dot [19] which, arguably, should be taught in every school on Earth, is a testament to altruism and compassion for life in all its forms.

Jonas Salk, who developed the first effective polio vaccine, famously declined to patent it, sharing his research freely with the world.[20] And he is hardly alone. Louis Pasteur, Marie Curie, Sir Isaac Newton, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, Nikola Tesla, Michael Faraday, Albert Einstein, Alexander Fleming, Inge Lehmann, Vera Rubin, Dmitri Mendeleev, Rosalind Franklin, Lise Meitner, Stephen Hawking, Niels Bohr, Erwin Schrödinger, Steven Weinberg, the list of scientists who have expanded our understanding of the universe is long and humbling. We also have living legends like Richard Dawkins, Sir David Attenborough, Lisa Randall, Arthur B. McDonald, Donna Strickland, Andre Geim, Kip Thorne, Heather Berlin, and many more. Countless scientists and engineers, undoubtedly driven by a mixture of curiosity, conviction, and altruism, have enriched our collective knowledge. And we must not overlook the philosophers, social scientists, and thinkers who, driven by the same restless inquisitiveness, have gifted us new frameworks for understanding ourselves: Francesco Petrarch, René Descartes, David Hume, Hannah Arendt, Bertrand Russell, James Randi, Noam Chomsky, Daniel Dennett, Baruch Spinoza, Steven Pinker, among others.

Of course, not all of these individuals were paragons of virtue. To pretend otherwise would be intellectually dishonest. Yet it is equally dishonest to assume that those with a charming disposition must also be altruistic, or that altruism cannot coexist with ambition or imperfection. Now, suppose for a moment that space exploration is entirely devoid of altruistic value. If we accept that premise, we must logically extend it to all human activities, whether undertaken individually or collectively. And such a universal cynicism would leave us with very little worth defending. Finally, I will close with one personal and admittedly cynical (perhaps arrogant) remark, followed by a quote from Stephen Hawking:

“Yes, space exploration is worth every penny and perhaps even more than we deserve, given how we use the very technologies developed through such research to complain about its inefficiencies.”

And, as Hawking wrote:

“We need to explore the solar system to find out where humans could live. In a way, the situation is like that in Europe before 1492. People might well have argued that it was a waste of money to send Columbus on a wild goose chase. Yet the discovery of the New World made a profound difference to the Old… It won’t solve any of our immediate problems on planet Earth, but it will give us a new perspective on them and cause us to look outwards rather than inwards. Hopefully, it will unite us to face the common challenge.”[21]

Next part: TB reedited

[1] These are the words that astrophysicist Carl Sagan used at beginning of his book Pale Blue Dot; Carl Sagan: Pale Blue Dot: A vision of the human future in space (New York, Ballentine Books; 1997).

[2] Here I count all activities made by public and some private space agencies (e.g. SpaceX) which are making huge steps toward better understanding of nature and pushing further development in perfecting of many known and future technologies.

[3] World Population Clock: 7.9 Billion People (2021) – Worldometer (worldometers.info); ; last time acquired 08.12.2021

[4] Such projects are already underway. The “ITER” (What is ITER?) is one of the boldest projects, concerning production of energy based on Tokamak fusion reactor (High-field pathway to fusion power | Research | MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center); Why the promise of nuclear fusion is no longer a pipe dream – BBC Science Focus Magazine; last time acquired 08.12.2021

[5] pollution | National Geographic Society

[6] Litter Definition & Meaning | Dictionary.com

[7] For now, we deal with zero gravity planes for a few seconds. We came up with this solution because we wanted to fly higher and into space. Without the motivation to overcome obstacles in one grand idea, one cannot expect to come up with an effective solution for the grand idea itself at all.

[8] Ancient DNA confirms Native Americans’ deep roots in North and South America | Science | AAAS; last time acquired: 02.01.2019

[9] Brief History of Syphilis (nih.gov); last time acquired: 23.07.2016

[10] One does not have to be a historian in order to understand that conflicts occur everywhere. In Africa or Asia for instance there are ongoing conflicts that predates any European presence or influence.

[11] i.e. Why was the ancient city of Cahokia abandoned? New clues rule out one theory. (nationalgeographic.com); last time acquired 08.12.2021

[12] An Example: About costs and Benefits of space exploration: Is It Worth It? the Costs and Benefits of Space Exploration (interestingengineering.com); last time acquired 10.12.2021

[13] We are simply unable to make certain (mathematical) future predictions about social processes, like the general theory of relativity did concerning gravitational waves (LIGO Project). At best, what we can do is emphasize the most probable outcome based on overall historical experience. As an exemplary argument for this claim, one can simply take a vast number of political secession movements which usually ended in bloodshed, yet there are those which ended extremely peacefully as well. It means that the higher the level of certainty in scientific prediction, the closer the specific discipline is to the spectrum of core sciences.

[14] Space race: Inventions we use every day were created for outer space (usatoday.com) and infographicsuploadsinfographicsfull11358.jpg (1000×8783) (d2pn8kiwq2w21t.cloudfront.net); last time acquired 10.12.2021

[15] James Webb Space Telescope Launch Media Kit (nasa.gov); last time acquired 26.12.2021

[16] How much do rockets pollute? | Everyday Astronaut; last time acquired 10.12.2021

[17] Roston, Michael (28 August 2015). “NASA’s Next Horizon in Space”. The New York Times; Retrieved 28 August 2015

[18] One need only to look at the inventions they are making. For example, SpaceX could easily do less in inventing and improving technology and still be one of the strongest private space organizations. Yet, the reality shows something else: new, more effective, and nature-friendly engines, energy conservation technologies, and solutions.

[19] “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there–on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.! — Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot, 1994; https://www.planetary.org/worlds/pale-blue-dot; last time acquired 10.12.2021

[20] https://www.salk.edu/about/history-of-salk/jonas-salk/; last time acquired 10.12.2021

[21] Stephen Hawking: Brief answers to the big questions (London, John Murray (publishers); 2020); pp.165-166.

One thought on “SCIENTIFIC (IL)LITERACY AND ITS SOCIAL CONSENQUENCES (Pt.2/3) Edition 2025”

Comments are closed.